‘All writers have a restlessness from a young age,’ says B. Jeyamohan

| Photo Credit: B. Jothi Ramalingam

In 2003, author B. Jeyamohan was travelling by bus when he instantly remembered Thimmappan. The reminiscence of a expensive good friend stricken with leprosy, and of a troubling previous that he had consciously repressed, overwhelmed him.

Jeyamohan received off the bus, went dwelling and commenced typing feverishly. In simply seven days, he accomplished Ezhaam Ulagam, a 287-page gut-wrenching story about a begging cartel.

The novel was revealed inside 4 days of submission and made its solution to a book exhibition the identical week. In 2009, Ezhaam Ulagam — praised by some for its unapologetic rawness and criticised by others for an “exaggerated” depiction of violence — was tailored for the display screen as Naan Kadavul. The movie went on to win two National Film Awards.

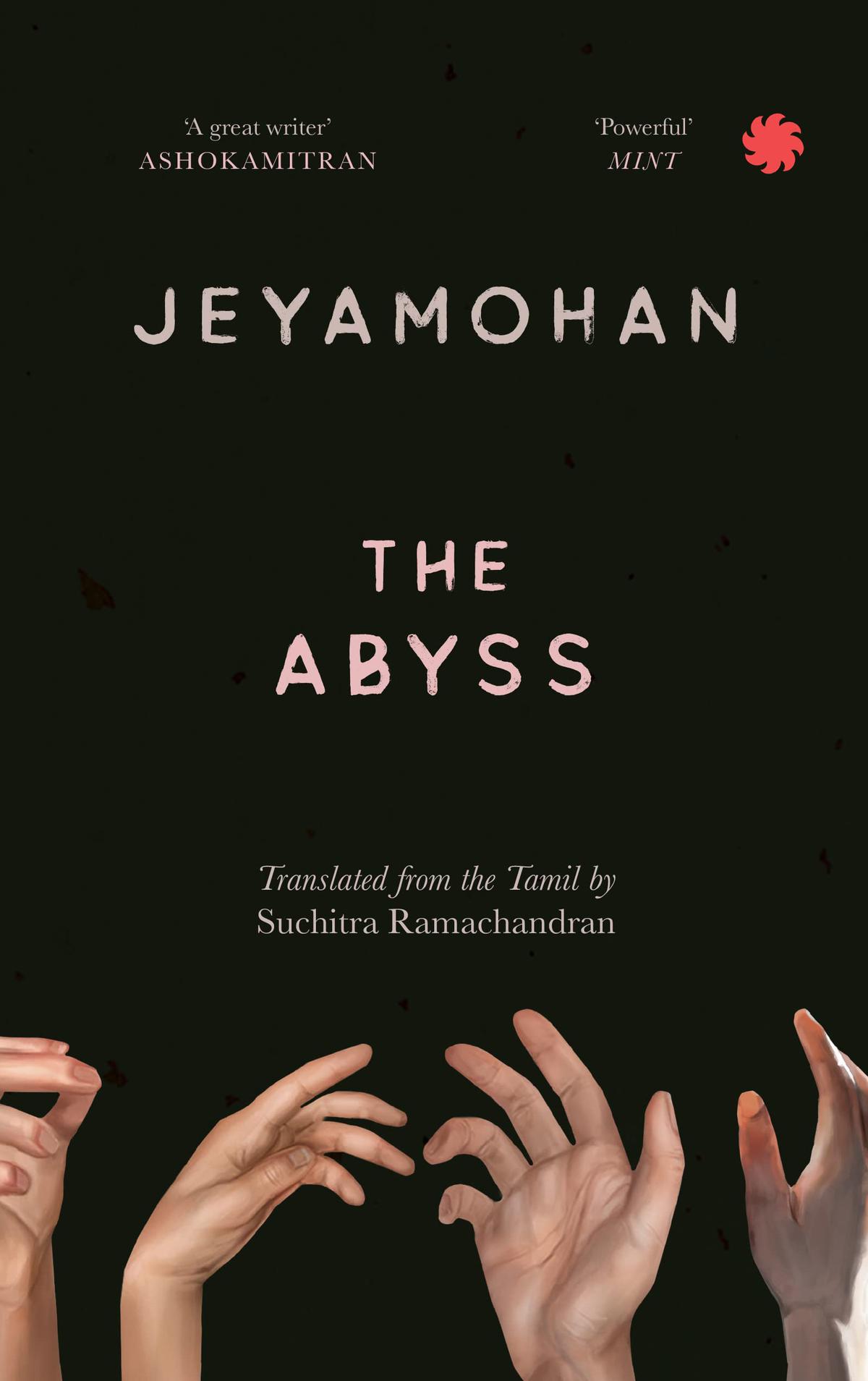

Twenty years after that bus journey, and hours earlier than final month’s trailer launch of Mani Ratnam’s magnum opus Ponniyin Selvan – 2, for which he’s a screenplay author, Jeyamohan, 61, makes the startling admission in an interview with the Magazine that he has by no means learn Ezhaam Ulagam. Nor has he learn The Abyss, its deft English translation by Suchitra Ramachandran, due for launch on April 10. The recollections of the years that impressed the book are too painful, he says. Writing about them was an act of catharsis.

Tamil author and critic B. Jeyamohan on his new book The Abyss

When he was 19, Jeyamohan ran away from dwelling. “All writers have a restlessness from a young age,” he says in a measured tone that belies any signal of a restive thoughts. “I had that. I left home four to five times. Once, I left because I was devastated by the suicide of a friend. And I lived as a beggar in Kashi, Tiruvannamalai and Palani.”

Exploring the darkish underbelly of society

The Abyss relies on his experiences in Palani. There are seven underworlds in response to Hindu mythology. The seventh world, or ezhaam ulagam, is inhabited by disabled beggars and characterised by egregious exploitation and cruelty. In Jeyamohan’s work, the beggars search out the fun of life even as they endure nice struggling. It is a deeply intense book that requires, of all issues, braveness to learn.

The protagonist, Pothivelu Pandaram, is a temple employee who trades in bodily deformed beggars or “items”. Even although Pandaram treats them as wretched beings and inflicts unimaginable violence upon them, such as forcing them to provide start to deformed infants or stuffing them into vans meant for transporting human waste, he’s a protecting father at dwelling, determined to fulfil the needs of his three daughters.

An previous man waits for alms by the roadside in Chennai.

| Photo Credit:

B. Jothi Ramalingam

While at the least 4 characters in the book are impressed by folks he has met, Jeyamohan says he didn’t personally know the person who impressed the character of Pandaram. He had heard of him from a analysis scholar good friend. “There are people like Pandaram in the world,” he says. “They may even kill children, but they go home to their own without guilt. They justify this in many ways. Pandaram doesn’t see his profession as a sin. He thinks he is doing the right thing by at least taking care of those who are orphaned.”

Even in this story in regards to the darkish underbelly of society, Jeyamohan weaves in empathy, tenderness and humour. In one shifting occasion, the beggars pool the little cash they’ve to make sure that Kuyyan, certainly one of their very own, will get a feast that he has been longing for lengthy. “Beggars may live in the abyss of our society, but they are still human beings,” Jeyamohan says. “They show magnanimity, forge friendships, have a social consciousness, and are spiritual.”

The world in the book is way faraway from what we all know or wish to perceive. But this world is round us, and “we just choose to ignore it”, says Jeyamohan. Is actuality so distressing? He stresses that it’s far worse. “This is an artwork, not a documentary. In fact, I have reduced the morbidity considerably. When the Tamil novel came out, there was accusation that it is cruel. But within four weeks, in Chennai, policemen found a team of seven people, including four women, dismembering children and selling them. That is reality.”

Writing for the display screen

The dialog returns to his frenzied strategy of writing. Recently, he wrote 120 pages at a go in about 36 hours, he says. Jeyamohan’s strategy is straightforward, although fairly drastic: “Write for hours. And if you get stuck, simply delete the entire draft.” Not many could ascribe to it.

Jeyamohan has greater than The Abyss to look ahead to this month. Though a reluctant participant in the promotion of Ponniyin Selvan – 2, he’s eagerly awaiting the discharge of the movie, which he describes as Mani Ratnam’s finest.

How did he adapt a magnum opus for the display screen? “In a book, you have thoughts and eloquence. But in cinema, you can convey all that only through visuals. Aditya Karikalan has many adjectives to his name in the book. In the film, we see him emerging from clouds and smoke. That shot establishes him as a godly figure. Once you understand this grammar, you take from the novel what fits the medium of cinema. I chose the major characters and events,” he says.

Jeyamohan can also be pleased that director Vetri Maaran’s new movie Viduthalai Part 1, primarily based on his quick story Thunaivan, is doing properly in theatres in Tamil Nadu and elsewhere. He is equally excited that a few of his different works, such as his memoir Purappadu, are in the method of being translated to English.

His output throughout mediums is undoubtedly formidable, however Jeyamohan is hungry for extra. He says he’s nowhere as prolific as Honoré de Balzac, Leo Tolstoy, Richard Wagner or Friedrich Hegel. But he isn’t nervous about working out of steam. “I have had spells of not writing,” he says. “But ideas… they always eventually come to me.”

radhika.s@thehindu.co.in