This article is a part of a fortnightly column exploring modern ideas and points in genetics.

The ‘black death’, or the Great Plague, of the 14th century was one of many deadliest epidemics in human historical past. It’s a transparent instance of the profound affect infectious disease outbreaks can have on society, economic system, and tradition. It was additionally most likely one of the crucial impactful epidemics, contemplating it left an indelible mark on humankind and formed the collective reminiscence of many subsequent generations.

The ‘black death’ is believed to have killed greater than 25 million individuals in Europe and presumably as much as 40-50% of the inhabitants in a few of the continent’s main cities.

What is the ‘black death’?

The ‘black death’ was attributable to a bacterium known as Yersinia pestis, which infects mammals. This micro organism’s discovery has been attributed individually to Alexandre Yersin, a Swiss-French doctor, and Kitasato Shibasaburō, a Japanese doctor and microbiologist through the plague outbreak in Hong Kong in 1894. Humans usually get contaminated by means of fleas or by means of shut dealing with/contact with an contaminated human or animal.

One doable motive for the humongous proportions of the ‘black death’ outbreak is the human-to-human transmission of the micro organism. While the plague stays a severe disease at the moment, it’s additionally fairly treatable. After the invention of antibiotics, in reality, its trendy mortality is sort of small.

India has skilled plague epidemics of various intensities from as early as 1896 in Bombay to outbreaks in Karnataka (1966) and Surat (1994), and to a newer remoted outbreak (2004) in a village in Uttarakhand. India additionally prominently figures within the historical past of the plague. The plague vaccine was developed by Waldemar Haffkine in 1897 through the outbreaks in Bombay; the nation additionally initiated mass vaccination programmes, with no less than 20 million doses estimated to have been administered so far.

How can we examine the historical past of a disease?

While the ‘black death’ might be not the earliest recorded epidemic, there are outdated data of its prevalence. Historical archives counsel the Plague of Justinian within the sixth century A.D. was presumably the primary to be documented. Plague epidemics proceed to happen around the globe and are at the moment endemic in some areas.

Bones of victims of the ‘black death’ in Martigues, France, as seen on December 1, 2011.

| Photo Credit:

S. Tzortzis/CDC, public area

The proof additionally means that plague outbreaks had been presumably widespread in Asia and Europe as early because the Late Neolithic-Early Bronze Age (LBNA), as implied by genetic materials remoted from a Swedish tomb dated to 3000 BC.

The LBNA interval is estimated to have lasted 5,000-2,500 years earlier than current. This period was additionally characterised by human contact, alternate throughout Europe, and a consequent social, financial, and cultural transformation of human society.

The creation of genome-sequencing applied sciences has allowed scientists to hint the path of infectious illnesses that ailed individuals in prehistoric instances. This is feasible specifically attributable to deep-sequencing of genetic materials remoted from well-preserved human stays, with the assistance of superior computational evaluation. Deep-sequencing entails sequencing the genomic materials a number of instances to retrieve even small quantities of DNA, for the reason that materials is more likely to degrade over time.

What has deep-sequencing revealed?

Scientists have additionally traced the prehistoric path of many main human pathogens in recent times, offering an unparalleled view of the evolution and adaptation of human pathogens.

Consider, for instance, a paper revealed in iScience on May 2. Researchers screened greater than 500 tooth and bone samples for genetic materials akin to Yersinia pestis. They recognized 5 human people from whom the genetic materials may very well be remoted, and constructed the genome of the pathogen with deep-sequencing.

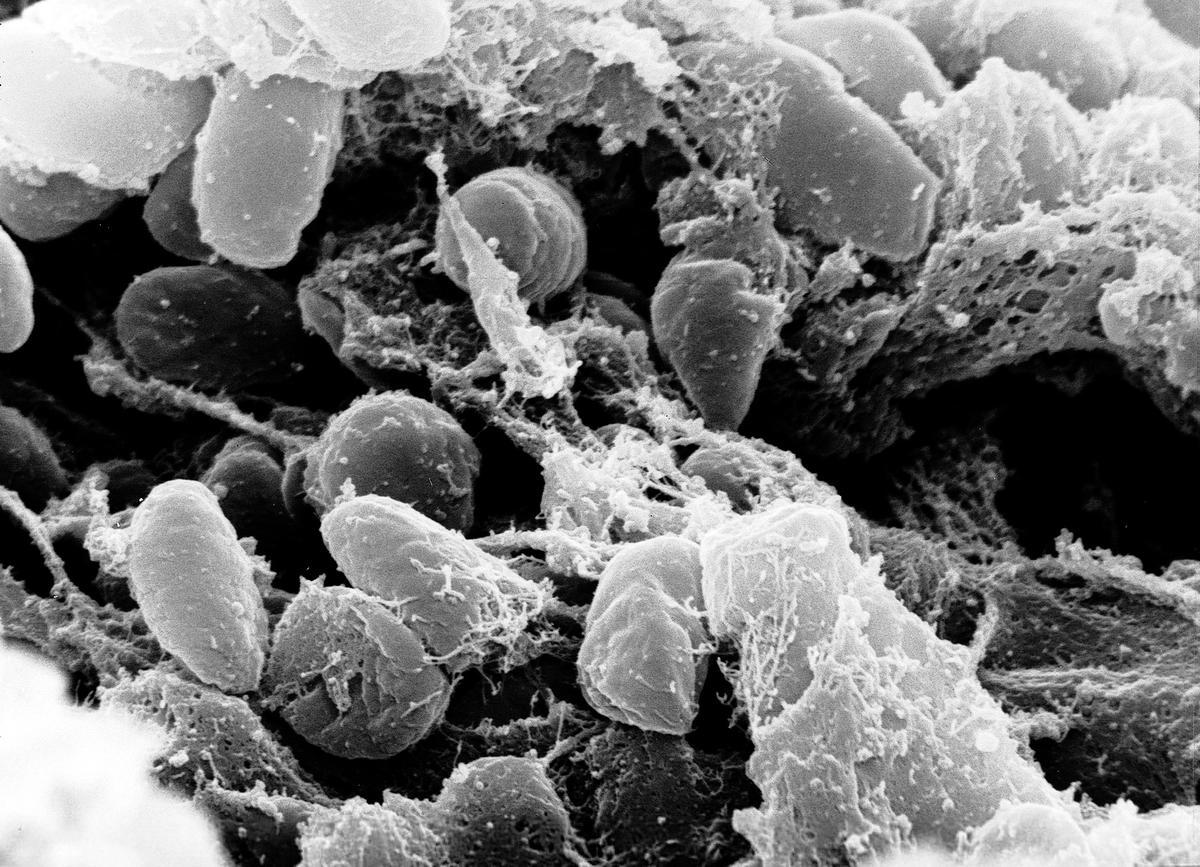

A scanning electron micrograph of Yersinia pestis micro organism in a flea.

| Photo Credit:

Public area

They discovered that the reconstructed genomes lacked the gene to create a molecule known as yapC, quick for ‘yersinia autotransporter C’, related to the micro organism’s capacity to bind to mammalian cells and kind biofilms – and thus necessary for inflicting infections. They additionally didn’t discover the gene for ymt, quick for ‘yersinia murine toxin’, which is required for the micro organism’s transmission by means of fleas. However, in addition they discovered the presence of a purposeful urease D gene, which may make them poisonous to fleas.

In one other current paper, revealed in Nature Communications on May 30, researchers on the Francis Crick Institute, London, reported sequencing genetic materials from two distant burial websites within the U.Okay. They studied 34 human stays within the Charterhouse Warren in Somerset and a hoop cairn monument in Levens Park, Cumbria. The stays had been estimated to be round 4,000 years outdated, overlapping with the LBNA interval. They recognized the genetic materials for Yersinia in three people, confirming the presence of epidemics in Britain within the LBNA, widening the geographical unfold of infections properly past Eurasia.

What does this educate us about our previous?

The genome sequences from the latter additionally lacked the yapC and ymt genes, reinforcing the earlier findings that the plague in that interval was presumably not transmitted by means of fleas.

Indeed, the earliest isolates of Yersinia pestis with the ymt gene, and thus tailored for flea transmission, had been presumably from samples from Russia and Spain estimated to be round 3,800 years and three,300 years outdated, respectively. The LBNA lineage of Yersinia is due to this fact believed to have been delivered to Europe by the migration of people from the Eurasian grasslands.

The broad geographical unfold over a protracted timespan additionally means that the plague was presumably fairly transmissible prior to now, although we all know little or no of its severity.

A typical costume of a “plague doctor” of sixteenth and seventeenth century Europe. The beak-like masks would maintain aromatic herbs following the assumption that good smells may negate disease.

| Photo Credit:

Peter Kvetny/Unsplash

As genome-sequencing has change into extra democratised, its functions are more and more enabling quick, environment friendly analysis of outbreaks, in routine scientific settings as properly, rapidly changing the standard approaches in microbiology. Sequencing gives monumental benefits over typical approaches as a result of it could possibly contribute to identification and molecular characterisation, and open home windows into virulence, antimicrobial and antibody resistance, and clues into the evolution, adaptation, and introduction of species in new settings.

The ambit of such applied sciences can be increasing to incorporate research of animal and plant illnesses, together with human illnesses, contributing to the unified understanding of our well-being known as ‘One Health’.

Sridhar Sivasubbu and Vinod Scaria are scientists on the CSIR Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (CSIR-IGIB) . All opinions expressed are private.