In a latest opinion article, Economic Advisory Council member Shamika Ravi article raised issues about the standard of information that India’s nationwide surveys – the National Sample Survey (NSS), the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), and the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) – gather.

Dr. Ravi raises two important points: overestimation of rural populations and totally different response charges throughout wealth teams proxied by revenue/expenditure, with decrease response charges in wealthier teams. The mixed inference is that these surveys could also be biased in direction of underestimating city, wealthier teams.

There are high quality points

We agree that Dr. Ravi has legitimate issues about information high quality and about representativeness or generalisability. It can be protected to imagine such points should concern solely the statisticians aiding the survey design or the researchers and analysts utilizing these information for insights. But Dr. Ravi means that these points concern us all as a result of they “systematically underestimate India’s progress and development”.

If we agree on the existence of information high quality points, we should assess their magnitude. The two factors of dialogue on the overestimation of the agricultural inhabitants are its depiction and the extent.

Truncated axis

Other responses to Dr. Ravi’s article have famous that an accompanying graph, depicting the agricultural inhabitants share, was deceptive as a result of the x-axis had been truncated. Dr. Ravi has responded that the “grammar of graphics” helps her visualisation selection. We disagree. Truncating an axis, particularly with out specific breaks or an accompanying rationalization, is a well-documented drawback.

Multiple research have proven that axis truncation results in a distorted notion of the impact measurement, i.e. readers view variations to be bigger than they are surely. Leading scientific publishers, together with Nature and the American Medical Association, advise towards truncated axes.

(For all dialogue beneath, we deal with NSS information, however related outcomes will be demonstrated for PLFS and NFHS information as properly.)

We created Dr. Ravi’s rural overestimation graph ab initio (determine 1). We calculated estimates for eight NSS surveys and took Census-based projections from the Report of the Technical Group on Population Projections (RTG-PP; 2019). All the info used and the scripts are obtainable right here. Comparing this determine with the one in Dr. Ravi’s article exhibits that the variations between projections and survey estimates appeared bigger there than they are surely.

Figure 1

| Photo Credit:

Special association

The error bars for the estimates in Dr. Ravi’s determine are additionally extra unfold out than they should be. Sampling errors for fundamental variables like inhabitants develop into very small with giant pattern sizes in such surveys.

Acceptable overestimation

The distinction within the survey estimates and projections for the agricultural inhabitants fraction vary from 2.57% factors to 4.40% factors. This brings us to the more difficult dialogue: How a lot overestimation of the agricultural inhabitants is suitable – 1%, 3%, 5%? This is a troublesome technical drawback.

A number of days after Dr. Ravi’s article appeared, she and her collaborators launched a working paper making an attempt to reply this query. They utilized a metric known as information defect correlation. They assessed the overestimation of rural and different inhabitants teams in two elements of the NSS 68 survey (2011-2012): ‘Household Consumption Expenditure’ and ‘Employment-Unemployment’. They used the 2011 Census information because the reference or a ‘ground truth’.

Although Dr. Ravi didn’t use the metric in her article, it follows the same custom of evaluating the Census-based projections with pattern survey estimates. The drawback right here is that the info defect correlation metric isn’t constructed to permit survey estimates to be in comparison with projections as a result of projections can’t be taken as dependable reference So, evaluating inhabitants projections and survey estimates wouldn’t inform us something helpful about information high quality.

Response charges

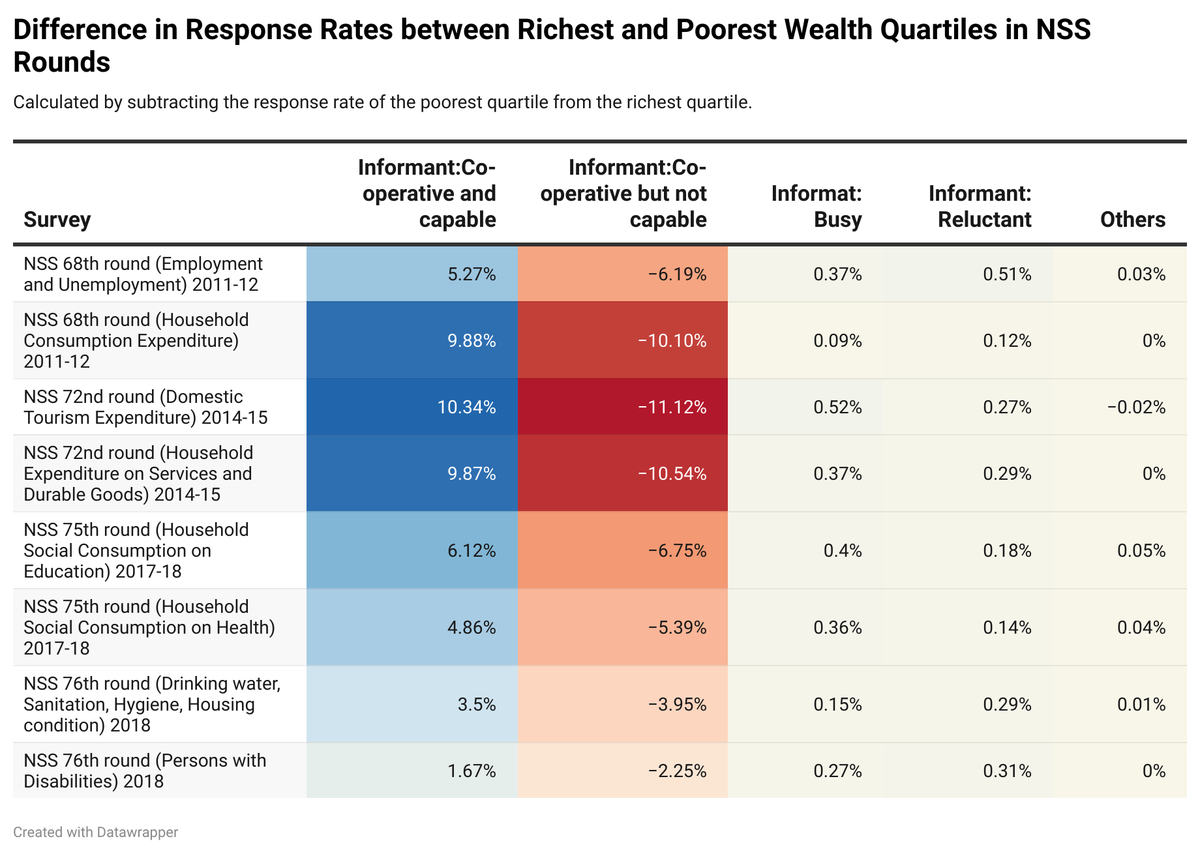

The second concern is the differential response charges throughout wealth teams. The validity of this concern depends upon the magnitude of such variations. We analysed nationwide estimates for a number of response classes throughout wealth quartiles in eight NSS surveys.

Figure 2 exhibits the variations between response-rate estimates for the richest and the poorest quartiles for every response class. The constructive variations within the fraction of respondents who had been cooperative and succesful between the richest and poorest quartiles denote a disagreement with Dr. Ravi’s concern.

Further, the percentage-point distinction within the fraction of reluctant respondents between the richest and poorest quartiles varies from 0.12% to 0.51% whereas that for busy respondents ranges from 0.09% to 0.52% throughout surveys. So, the response charges for these classes are negligibly totally different.

Figure 2

| Photo Credit:

Special association

The unfavorable variations additionally present that respondents who’re cooperative however not succesful belong extra to the poorest than the richest quartiles. So there’s restricted cause to consider that the responses from the wealthier sections of the inhabitants had been considerably discounted within the NSS.

Scholarly response

Data high quality issues about surveys all all over the world are sometimes raised by these working with them. Xiao-Li Meng, who originated the info defect correlation metric, has usually criticised the standard of information produced by U.S. surveys. People have additionally famous different issues with the NSS, reminiscent of non-representativeness and non-coverage points in some Indian states, discrepancies in intercourse, marital standing, and different variables, going again to 1988. Demographic and well being surveys – of which the NFHS is a sort – have been criticised for biases in stillbirth and early neonatal mortality as properly.

But these issues have additionally been justified via rigorous analyses adopted by scholarly editorial checks and peer-review, earlier than being launched to the folks at giant. Further, such cautionary flags have nearly at all times been accompanied by direct corrective measures to assist these coping with these information. In truth, devising methods to cope with numerous points in survey information is an energetic space of analysis in India and past.

Maturity of strategies

This mentioned, the concept giant surveys will be non-representative and induce bias because of this is new. Professor Meng’s technique of quantifying such bias is just 5 years previous and was first utilized to a main instance in vaccination surveys within the U.S. solely two years in the past. Researchers want extra time for these strategies to mature and to be adopted within the applicable contexts. Only then can they inform essential modifications.

For instance, if researchers discover that part of the agricultural overestimation bias is because of an absence of the suitable sampling body, given the 2011 Census is 13 years previous now, we are going to want Census 2021 to be undertaken and accomplished posthaste to enhance the info high quality. In this sense, we agree with Dr. Ravi that discussions, and actions if warranted, round information high quality are the necessity of the hour.

Most Indians stay in rural areas

Our remaining concern is about a suggestion in Dr. Ravi’s article, articulated as “gap between ground realities and survey estimates”, “population projections falling short of rapid pace of change on ground”, and that “these surveys grossly and systematically underestimate India’s progress and development”.

A query arises: if no information (from surveys or projections) seize fast urbanisation, how can we declare that it exists? Our personal work has discovered robust settlement between modelled information from dependable worldwide sources and India’s Census-based projections for whole, rural, and concrete populations for 2017.

Dr. Ravi’s suggestion that “progress” in different dimensions, together with well being, wealth, and social improvement, which can be tied to urbanisation is being underestimated opens the door to a extra significant issue: that of rural-urban disparity. That is, if our rural populations did in addition to city populations on all such indicators – overestimated or not – there wouldn’t be any issues about systematic underestimation of enhancements throughout the financial system.

But information from numerous sources verify that rural India lags behind its city counterpart, which makes its overestimation an issue past the legitimate data-quality issues. Focusing on rural-urban disparities in well being, wealth, and many others. is important given all of us agree that almost all Indians stay in rural areas.

In his 2018 paper, Prof. Meng famous that his curiosity within the representativeness bias drawback arose from the query, “Which one should we trust more, a 5% survey sample or an 80% administrative dataset?” The corollary right here could be: Which one should we belief extra, biased survey estimates or unsupported optimistic speculations about on-ground progress?

Siddhesh Zadey is cofounder of the non-profit think-and-do tank Association for Socially Applicable Research (ASAR) India and a researcher on the Global Emergency Medicine Innovation and Implementation (GEMINI) Researcher Centre, Duke University US. Pushkar Nimkar is an engineer turned economist at the moment volunteering as a knowledge analyst with ASAR. He additionally works on the Department of Economics at Duke University. Parth Sharma is a doctor and a public well being researcher who volunteers at ASAR. He can also be the founding father of Nivarana.org.