With the BJP-led authorities exuding over-confidence on the state of the economy, the interim Budget offered earlier this month has shifted focus to fiscal consolidation. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has projected that the fiscal deficit; which was expanded to 9.2% of GDP in 2020-21 to take care of the pandemic-induced recession; can be introduced down to five.8% by the finish of the present monetary 12 months and 5.1% by subsequent 12 months to succeed in the focused 4.5% of GDP by 2025-26.

The interim Budget indicators vital cutbacks in public expenditures, slashing efficient capital expenditure by ₹1 lakh crore and lowering welfare and subsidy allocations. Despite a nominal GDP development of 9%, down from the earlier 12 months’s 10.5%, the authorities faces challenges with a slowdown in economic exercise. Real GDP development stands at 7.3%, above final 12 months’s 7.2%, whereas the IMF questions the accuracy of official development estimates, recommending statistical upgrades. The fiscal state of affairs is sophisticated by rising debt liabilities, marking a proper withdrawal of post-pandemic stimulus in the interim Budget.

Added to that is the prospect of a slowdown in economic exercise, relating to which the authorities appears to be in denial. Despite the nominal GDP development fee falling to 9% in the present 12 months from 16% final 12 months, actual GDP development (at fixed costs) has been estimated at 7.3% (superior estimates), barely above the 7.2% registered final 12 months, implying that the worth of the GDP deflator — which ought to correspond with the retail inflation fee — has fallen beneath 2% in 2023-24. Official information, on the different hand, exhibits the month-to-month common of client worth inflation (Consumer worth index-CPI-combined) at 5.5% for 2023-24.

This anomaly has as soon as once more revived the debate over the accuracy of official development estimates. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), in its newest employees report on India (November 2023) has identified a number of defects and deficiencies in actual sector information, notably that of nationwide accounts, employment, and costs, recommending an upgradation and enlargement of official statistics. It is noteworthy that in its January 2024 Update of World Economic Outlook, the IMF has projected India’s actual GDP development as 6.7% for 2023-24 and 6.5% for 2024-25, reflecting a deceleration of economic exercise.

Budget and Public Finance

The Finance Minister has sought to divert consideration from this debate over the current path of change in economic exercise, by presenting a “White Paper” in Parliament on the previous twenty years. The white paper alleges that the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) had left behind a “deeply damaged economy” marred by “governance, economic and fiscal crises” in 2014, which is claimed to have “turned around” and “rebuilt” from its foundations in the previous 10 years by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) regime. The proof offered in assist of this macroeconomic narrative, nonetheless, is a concoction of cherry-picked information, half-truths, evasions, and counter-factual assertions. The 55-page doc mentions the phrase “inflation” 17 occasions, whereas the phrase “jobs” is talked about twice, “employment” solely as soon as and “unemployment” by no means in any respect; which exposes the skewness of its evaluation.

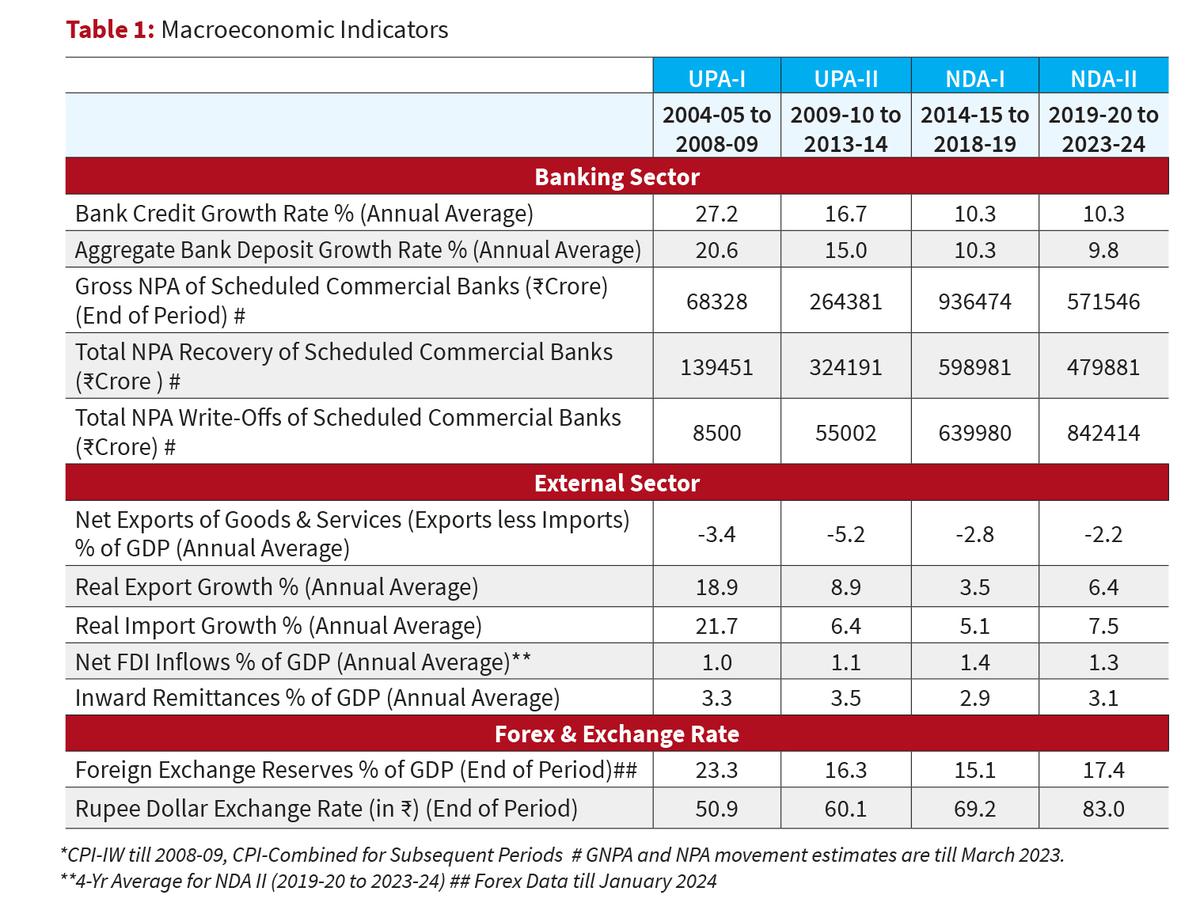

Over the previous 20 years, fiscal tendencies present no clear sample between UPA and NDA regimes (See Table 1). NDA-I lowered expenditures as a share of GDP, whereas NDA-II elevated spending considerably post-pandemic. NDA-II’s expenditure file is blended in comparison with UPA, with enhancements in sure areas however declines in others. The NDA-I authorities had lowered expenditures relative to GDP on most main heads in comparison with the UPA regime, together with capex, subsidies, defence, training and rural improvement. NDA-II elevated the outlays on these heads considerably vis-a-vis NDA-I. However, the expenditure file of the NDA-II authorities vis-a-vis the UPA period stays blended; outlays on capex, meals subsidy, agriculture, and city and rural improvement improved, whereas outlays on training, defence and subsidies on gasoline and fertilizer fell, as per cent of GDP. Health expenditure as a share of GDP noticed no change in any respect between the UPA and NDA rule, regardless of the pandemic.

On the income entrance, gross tax revenues in GDP confirmed minor enchancment throughout the NDA rule in comparison with UPA’s, however non-tax revenues deteriorated. Overall there was a decline in the Centre’s income receipts as a share of GDP, partly resulting from the enhance in the State’s share in Central taxes following the implementation of the 14th Finance Commission suggestions.

NDA’s income mobilisation technique revolved round rising oblique tax collections on one hand, by way of GST rollout and levying excessive excise duties on petro-products and increasing the revenue tax base on the different. Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) information present that the quantity of particular person revenue taxpayers with optimistic tax funds elevated from 1.25 crore in 2012-13 (evaluation 12 months) to 2.08 crore in 2021-22 (evaluation 12 months). The common tax paid per particular person revenue taxpayer greater than doubled from ₹91,200 to ₹2.03 lakh in 2021-22. This raised revenue tax revenues from the UPA years’ annual common of round 2% of GDP to 2.3% under NDA-I and 2.9% throughout NDA-II.

In sharp distinction, nonetheless, company tax collections fell as a share of GDP, from the UPA period common of 3.5% of GDP to three.3% under NDA-I and additional to 2.8% under NDA-II. Aggregate revenue tax collections are projected to surpass company tax collections by over ₹1.13 lakh crore in 2024-25.

CBDT information present the quantity of firms paying optimistic taxes rising from 3.45 lakh in 2012-13 (evaluation 12 months) to 4.57 lakh in 2021-22 (evaluation 12 months). Yet, information from the “Statement on Revenue Impact of Tax Incentives under the Central Tax System”, annexed with the Receipt Budgets, present that the efficient company tax fee, which inclusive of the dividend distribution tax had risen from 24.2% in 2012-13 to 30.4% in 2018-19, had fallen sharply to 22.2% in 2020-21.

The withdrawal of the dividend distribution tax and sharp discount in the company tax fee by way of the new tax regime launched in 2019-20, have led to huge income losses under the NDA-II authorities, whose estimates the authorities has suppressed until date. Such a income mobilisation technique, whereas transferring revenue from the poor (by way of enhanced oblique taxes) and center courses (by way of revenue taxes) to the profit-making company sector, in addition to exacerbating revenue inequality, has additionally did not generate enough revenues at a time when public expenditure was being enhanced under NDA-II, following the onset of the pandemic and recession.

As a outcome, the income deficit has ultimately bloated to a mean of 4.3% of GDP under NDA-II and the fiscal deficit averaging at 6.6%, elevating the central authorities’s debt from 52% of GDP at the finish of UPA rule and round 50% under NDA-I to the present degree of 58%. Annual curiosity expenditure has additionally risen from the low of 3.0% earlier to three.6% of GDP in the present interval, which the authorities is now making an attempt to reckon with, by slashing capex, subsidies and welfare expenditure in the interim Budget.

It can also be noteworthy, that regardless of the enhanced degree of sources transferred to the States in the previous 10 years, mixed debt of the State governments have grown quicker than that of the Centre under the NDA rule than the UPA period. This underlines the inadequacy of present degree of fiscal transfers to the States, given their increasing expenditure commitments.

Growth and inflation

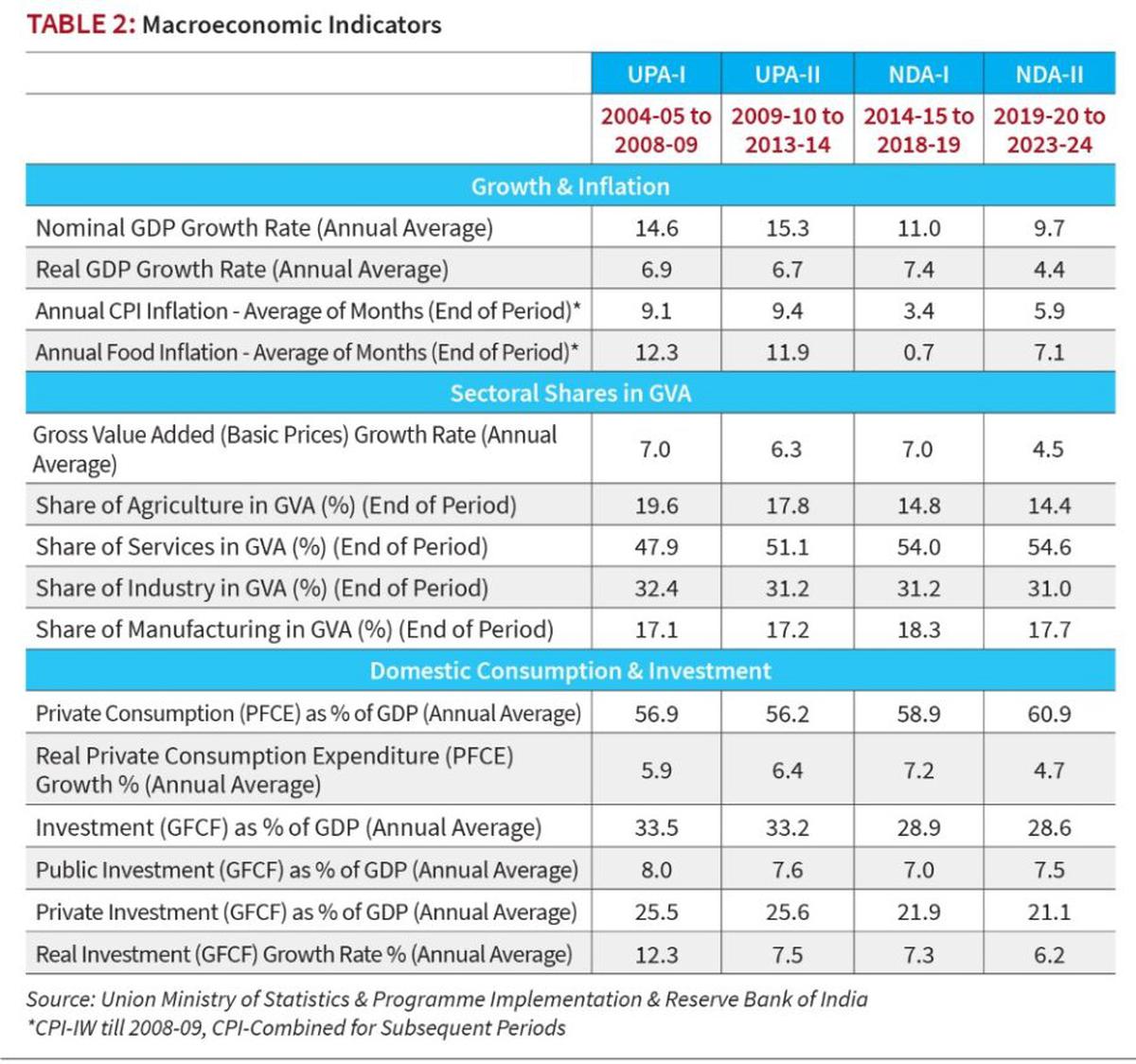

Official information on the actual economy under the NDA regime has been criticised from a number of quarters for overestimating its personal macroeconomic efficiency and undervaluing that of the UPA regime. Even then, the easy reality which is clear from the official information is that on common, actual GDP development was at the least one share level larger throughout the UPA decade than that of the NDA (See Table 2). Not solely did the deep droop following the pandemic and lockdown trigger main disruption throughout NDA-II, however slowdown in the economy was already evident under NDA-I after the successive coverage shocks of demonetisation and GST rollout. The UPA period had additionally witnessed the international monetary disaster and consequent worldwide recession in 2008-09, which was additionally a serious exterior shock.

Gross worth added (GVA) development in fundamental costs additionally mirror the similar pattern as actual GDP, with the common development fee first rising throughout UPA I, then falling throughout UPA II, rising once more in the NDA I interval and then falling sharply throughout NDA II. Most importantly, the ten years of NDA rule couldn’t present any break with the sectoral sample of development witnessed throughout the UPA period. Agricultural development remained method beneath the total GVA development fee, with its share in total GVA falling constantly. With the share of manufacturing and industrial sectors remaining largely the similar under UPA and NDA durations, the companies sector’s share in GVA elevated from beneath 48% in 2008-09 to over 54% in GDP. The Make in India initiative launched by the NDA, to remodel India right into a “global manufacturing hub”, couldn’t achieve altering the services-led development trajectory.

Real funding and export development was considerably larger throughout the UPA decade than the NDA’s, which explains the trigger of larger actual GDP development throughout the former regime, regardless of being interrupted by a worldwide recession. Private funding (GFCF) as a share of nominal GDP throughout the UPA decade remained considerably larger than the later interval. In distinction, development throughout NDA-I used to be personal consumption led. During NDA-II’s tenure, even actual personal consumption development fell considerably, making economic development largely depending on the fiscal stimulus. This is clearly borne out by the rising fiscal deficit and debt-GDP ratio under NDA-II.

UPA’s development file, though larger than NDA’s in magnitude, had three main drawback areas, which the Finance Ministry’s “White Paper” has highlighted. What is lacking although is an sincere appraisal of how far the NDA regime has been in a position to handle and resolve them.

The most problematic facet of UPA period’s development course of was the excessive inflation that accompanied it, notably the double digit meals inflation (Table 2). The new sequence of CPI information mirror a pointy decline in the total client inflation fee by the finish of NDA-I’s tenure to three.4%, however a resumption of the inflationary pattern under NDA-II, averaging round 6% yearly. As was the case with the UPA regime, NDA too has relied upon the Reserve Bank of India to strive and management inflation by elevating its coverage rate of interest and managing liquidity.

Despite the repo fee being hiked from 4% in mid-2020 to six.5% in February final 12 months, the place it has been held until date, the headline inflation fee has stubbornly ranged between 5-7% in the previous two years, with common meals inflation crossing 7% in 2023-24. This demonstrates, because it did throughout the UPA period, that RBI’s repo fee changes have little or no affect on meals worth actions in India.

The National Democratic Alliance (NDA) regime has completed little to deal with the main provide aspect elements driving meals inflation, past imposing advert hoc export bans. While money switch schemes like PM-Kisan or the distribution of free foodgrains to poorer households can present a lot wanted revenue assist and aid, they will neither enhance agricultural productiveness nor modernise storage and advertising and marketing of meals objects like greens, pulses and cereals, whose costs are driving meals inflation at this time. The solely methodology conceived by the NDA to deal with these points was to facilitate a wholesale company takeover of India’s meals and agricultural economy by enacting three farm legal guidelines in September 2020, which needed to be ultimately rescinded following a year-long protest by north Indian farmers. Since then, the NDA-II authorities has remained as clueless as the UPA (United Progressive Alliance)-II was, in coping with meals inflation and agriculture.

The second drawback with UPA’s development story was that whereas exports grew quickly, imports grew even quicker, partly resulting from rising international crude costs, which worsened the present account steadiness and elevated exterior vulnerability. During the NDA regime, each export and import development declined, which impacted economic development adversely however improved the exterior commerce steadiness. Further, throughout the NDA decade, internet FDI inflows elevated as a share of GDP however remittance inflows, which remained considerably larger than internet FDI inflows, declined in comparison with the UPA decade. The end-result has been blended.

The fall in India’s overseas alternate reserves throughout NDA-I may very well be reversed throughout NDA-II, however the rupee has continued to depreciate vis-a-vis the greenback. The rupee-dollar alternate fee, which fell from ₹43 to ₹60 per greenback throughout the UPA rule has fallen additional to ₹83 throughout NDA’s tenure. In the context of the post-pandemic surge in international inflation final 12 months, the rupee depreciation has solely imported the inflationary pattern into the home economy.

The drawback of NPAs

The third drawback with UPA’s larger development and personal funding section was that it led to rising huge ticket company defaults, initially hid by way of debt restructuring, which finally left an enormous pile of legacy Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) in the banking system. The Modi authorities is claiming credit score for restoring the well being of Public Sector Banks (PSBs) by lowering the Gross Non-Performing Assets (GNPA) inventory considerably. The truth stays that whereas cumulative NPA discount under the NDA rule by way of all restoration channels, together with the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code was round ₹10.8 lakh crore (until March 2023), NPA write-offs have amounted to over ₹14.8 lakh crore in the similar interval.

The PSBs, which accounted for over ₹10.65 lakh crore of these NPA write offs needed to take up substantial losses as a result of of NPA provisioning, making internet losses between 2017-18 and 2019-20. Simultaneously, since 2017-18 huge doses of capital was infused into PSBs and monetary establishments like the EXIM Bank, the Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI) and the India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL), in an effort to bail them out. As disclosed in the Receipt Budgets, the Centre’s complete debt burden on account of these recapitalisation bonds have elevated to ₹2.90 lakh crore by 2023-24, and their annual curiosity expense of over ₹19,000 crore is being met by way of the central authorities’s income expenditure since 2019-20. Bank recapitalisation under the UPA rule, which was of a a lot smaller magnitude, was audited by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG), overlaying the interval between 2008-09 to 2016-17. However, financial institution recapitalisation executed under the NDA rule has not been audited by the CAG to date. Such an audit is important to guage the huge NPA write offs by the PSBs and conclude whether or not personal sector debt defaults have been subsidised by way of the public exchequer.

Income and employment

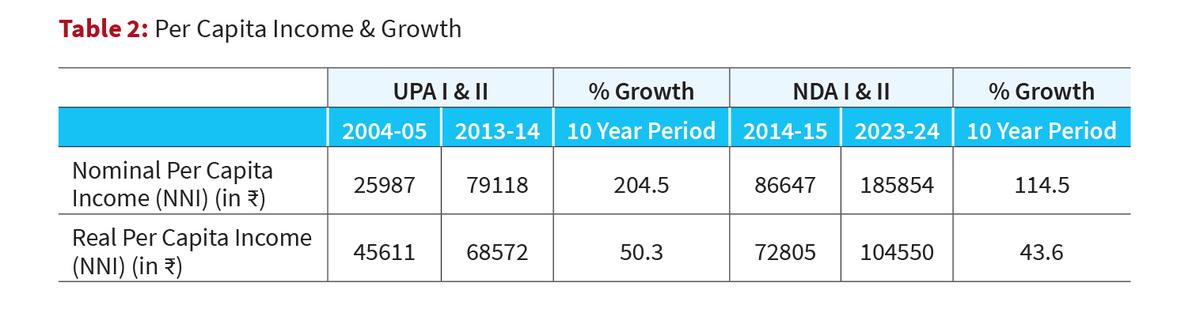

The efficacy of Union Budgets must be judged in phrases of their influence on the lives of unusual individuals. The Finance Minister has claimed in the Budget speech that under NDA rule “people are living better and earning better, with even greater aspirations for the future. Average real income of the people has increased by fifty per cent.” However, how true is that this declare? Official information exhibits that actual per capita revenue in India, estimated by the inflation-adjusted Net National Income (NNI), registered a development of 50.3% throughout the ten years of UPA rule. During NDA’s ten 12 months rule, actual per capita revenue grew by 43.6%, reflecting a slowdown in inflation adjusted revenue development throughout India.

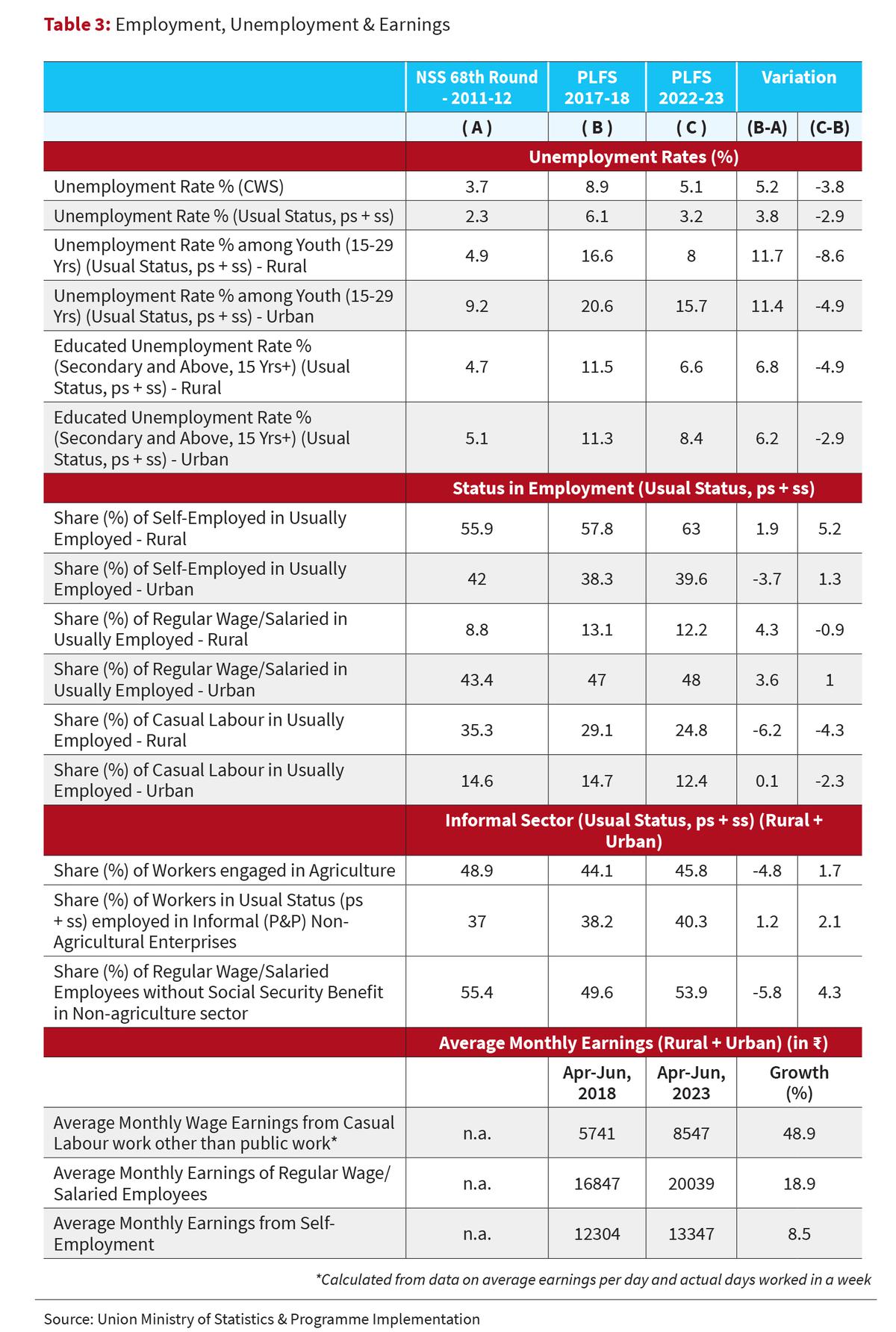

The NDA authorities usually cites the annual Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) findings to say a discount in the unemployment fee between 2017-18 and 2022-23. However, comparable estimates from the NSS 68th spherical on Employment and Unemployment Situation in India, exhibits that unemployment charges, estimated by each present weekly standing and adjusted traditional standing, grew very sharply between 2011-12 to 2017-18.

Moreover, whereas the unemployment charges declined between 2017-18 and 2022-23, the open unemployment charges of 2022-2023 had been nonetheless larger, not solely vis-a-vis the NSS 68th spherical of 2011-12, however in comparison with all the eight earlier NSS rounds carried out since 1972-73. The open unemployment charges have by no means been so excessive in India in the final 50 years. Unemployment was notably excessive amongst the city youth aged 15 to 29 years and amongst these with an academic degree of secondary and above. Within these employed, the share of informal employees present a declining pattern each in rural and city areas, whereas the proportion of self-employed have elevated progressively. In 2022-23, self-employed employees and helpers in personal account enterprises made up 63% of the rural labour pressure and virtually 40% of the city labour pressure. The share of common wage/salaried employees has declined in rural areas and elevated in city areas between 2017-18 and 2022-23. However, the share of these with none social safety profit has elevated inside the salaried employees class.

Even as agriculture’s share in Gross Value Added (GVA) has declined to 14.4% in 2023-24, there was a rise in the share of employees engaged in agriculture between 2017-18 and 2022-23. The share of employees engaged in casual non-agricultural enterprises has additionally elevated since 2011-12. These tendencies in employment standing from the PLFS information level in the direction of rising informalisation of the labour pressure, opposite to official claims of elevated formalisation.

Skilled however not employed

The Finance Minister had claimed in the Budget speech that the authorities’s “Skill India Mission” has educated 1.4 crore youth and 54 lakh youth have been up-skilled and reskilled. However, the dashboard in the official website of the PM Kaushal Vikas Yojana exhibits that out of 1.10 crore licensed candidates, solely 24.51 lakh, that’s round 22%, have been “Reported Placed”. Such extra provide of expert employees in the economy and rising informalisation is working as a dampener on wage and earnings development. PLFS information additional present that the common earnings of informal labour in private work to be ₹8,547 in 2022-23, that of self-employed employees to be ₹13,347 and that of common wage/salaried employees to be ₹20,039. While informal labourers’ common earnings has grown by round 49% in 5 years since 2017-18, and common wage/salaried employees by 19%, common earnings of self-employed employees rose by 8.5% solely in 5 years. With annual retail inflation fee averaging 6% throughout NDA-II’s tenure, lower than 2% annual development in common earnings for the self-employed clearly point out a decline of their actual earnings. 57% of India’s labour pressure engaged in self-employment, are actually not “living better and earning better”, as the Finance Minister would need us to imagine. It is their hopes and aspirations that stand betrayed.

Prasenjit Bose is an economist and activist; Indranil Chowdhury teaches economics at PGDAV school, DU; Samiran Sengupta and Soumyadeep Biswas are information analysts at CPERD Pvt. Ltd.