Eloor smells like it’s dying.

Once it was an island of wealthy farmland on the Periyar River, 17 km (10.5 miles) from the Arabian sea, teeming with fish. Now, a stench of putrid flesh permeates the air. Most of the fish are gone. Locals say folks residing close to the river are hardly even having youngsters anymore.

Yet right here is Shaji, alone in his small fiber boat, fishing along with his handmade rod, Kerala’s huge industrial smokestacks behind him.

Some 300 chemical corporations belch out dense fumes, nearly warning folks to keep away. The waters have taken on darkish hues. Shaji, a fisherman in his late 40s who solely makes use of one identify, is among the many few who stay.

“Most of the people here are trying to migrate from this place. If we look at the streets, it’s almost empty. There are no jobs and now we cannot even find work on the river,” stated Shaji, displaying the few pearl spot fish he managed to catch throughout a whole day in March.

Many of the petrochemical vegetation listed here are greater than 5 many years outdated. They produce pesticides, uncommon earth components, rubber processing chemical substances, fertilizers, zinc-chrome merchandise and leather-based remedies.

A polluted creek, a tributary of the Periyar River, is seen in Eloor, Kerala state, India, Saturday, March 4, 2023.

| Photo Credit:

AP

Some are authorities owned, together with Fertilisers and Chemicals Travancore, established in 1943, Indian Rare Earths Limited, and Hindustan Insecticides Limited.

Residents say the industries absorb massive quantities of freshwater from the Periyar and discharge concentrated wastewater with nearly no remedy.

Anwar C. I. is a member of a Periyar anti-pollution committee and a non-public contractor who lives within the space. He stated residents have grown accustomed to the reek that appears to grasp over the realm like a heavy curtain, enveloping all the pieces and everybody.

The groundwater is now totally contaminated and the federal government’s rivalry that the companies profit folks is fallacious, he stated.

Also Read | Near Kochi shore, rising salinity makes water unusable

“When they claim to provide employment to many people through industrialization, the net impact is that the livelihood of thousands is lost,” Anwar stated. People can’t make a residing from ruined land and water.

Residents have periodically risen up towards the factories within the type of protests. Demonstrations started in 1970, when the village first witnessed 1000’s of fish dying. Both die-offs and protests occurred once more many occasions after that, stated Shabeer Mooppan, a long-time resident who has usually demonstrated.

“Some of the early protest leaders are now bedridden” in superior age, Mooppan stated, emphasising simply how lengthy folks in the neighborhood have been making an attempt to get the river cleaned up.

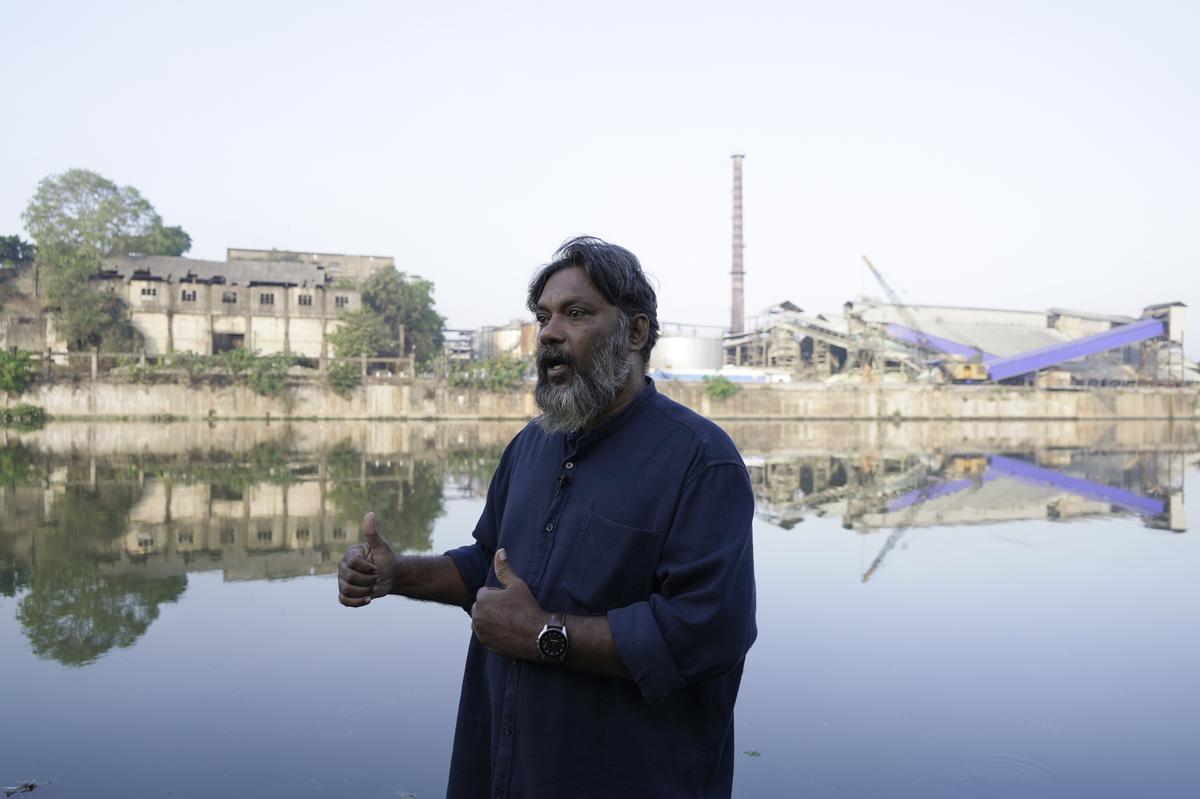

Anwar C. I., an official of the Periyar River anti-pollution committee, speaks throughout an interview alongside the river in Eloor, Kerala state, India, Friday, March 3, 2023. He stated residents have grown accustomed to the all-pervasive reek that appears to grasp over the place like a heavy curtain, enveloping all the pieces and everybody.

| Photo Credit:

AP

Now Shabeer is making an attempt to enhance surveillance, to catch these answerable for fouling the river. It’s a technique utilized by riverkeepers and baykeepers in different cities all over the world. He can also be pursuing authorized instances towards polluting industries.

The state Pollution Control Board downplayed the commercial air pollution within the Periyar River, blaming it on sewage from properties, industrial establishments and markets upstream.

“We have not found any alarming rate of metals in the river water. All the levels are within the limits,” stated Baburajan P Okay, chief environmental engineer of the board.

Baburajan stated solely 5 main corporations of the over 300 industrial vegetation within the area are allowed to discharge wastewater into the river, and it should be handled. The relaxation should deal with their wastewater, reusing or disposing it on their very own land. He stated hefty environmental levies have been imposed on violators.

Research additionally tells a narrative of a river in misery.

As far again as 1998, scientists on the Kerala University of Fisheries and Ocean Studies discovered some 25 species of fish had disappeared from the area. Experts have discovered contamination in greens, rooster, eggs, fruits and tuber crops from the area.

Chandramohan Kumar, a professor in Chemical Oceanography at Cochin University of Science and Technology, has researched Periyar River air pollution in a number of research.

“We have observed pollution from various organic fertilizers, metallic components. Toxic metals like cadmium, copper, zinc and all the heavy metals can be detected there,” Kumar stated.

Also Read | Centre launches Periyar river conservation challenge

A decade in the past, the National Green Tribunal ordered the federal government to create an motion plan to restore water high quality within the river to defend the atmosphere and public well being. It additionally ordered the formation of a monitoring committee.

More lately, the Tribunal was frightened sufficient to provoke its personal continuing on the air pollution. It cited research going again to 2005, carried out by the environmental non-profit group Thanal, that confirmed “hundreds of people living near Kuzhikandam Creek at Eloor were afflicted with various diseases such as cancer, congenital birth defects, bronchitis, asthma, allergic dermatitis, nervous disorders and behavior changes.”

Adam Kutty stands on the financial institution of the Periyar River with smokestacks within the distance in Eloor, Kerala state, India, Friday, March 3, 2023. Many of the petrochemical close by produce pesticides, uncommon earth components, rubber processing chemical substances, fertilizers, zinc-chrome merchandise and leather-based remedies.

| Photo Credit:

AP

The courtroom cited one other survey of 327 households within the area that confirmed hazardous chemical substances, together with DDT, hexachlorocyclohexane, cadmium, copper, mercury, lead, toluene, manganese and nickel had been discharged into Kuzhikandam Creek “and adversely affected the health condition of people in Eloor.”

Kumar stated the treatment for this air pollution is onsite remedy at every facility, and it comes down to cash. “If they are ready to invest, the effluent discharge can be resolved,” he said.

Also Read | 75% of river monitoring stations report heavy metal pollution: Centre for Science and Environment

The Pollution Control Board responded that it recently began a study that could lead to curbing air pollution and reducing the intolerable stench in the area largely caused, it said, by bone meal fertilizer factories and meat rendering plants. It is expected to be finalized in May.

The board dismissed allegations that it does not actively pursue polluters and said it ensures no untreated waste liquids are discharged into the river.

Trainees with the Pollution Control Board do daily trips to collect samples from six different points along the river.

“But we don’t know what happens to those samples,” stated resident Adam Kutty. “What’s the point of having all the money in the world and no water to drink?”

Omana Manikuttan, a long-time resident of Eloor, stated for years she and her neighbours haven’t eaten fish from the river. Eating them leads to critical diarrhea and tastes like pesticides, even after cooking, Manikuttan stated.

As the blame recreation continues, the grass and bushes within the space seem wilted as if scorched by the noxious fumes. The birds appear to have been pushed away by the air. Without official motion, the pall over the area and its residents is unlikely to carry quickly.

This article is a part of a sequence produced beneath the India Climate Journalism Program, a collaboration between The Associated Press, the Stanley Center for Peace and Security and the Press Trust of India.